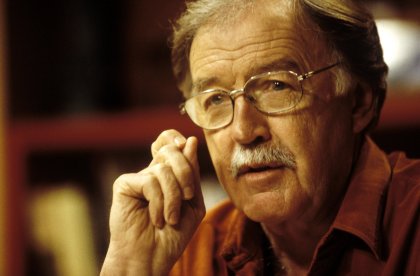

THE POVERTY BUSTERS: Grameen Bank founder Dr Muhammad Yunus - Wednesday 3rd October, 2007

It is the morning rush hour here in Dhaka, a clangourous place

of 11 million. Like most sub-continental Asian cities, Dhaka bustles

but today it's deceptively peaceful, given what's been going on in

these very streets of late. Back in August, thousands rioted here in

Dhaka angry at what they saw as the unelected government's reluctance

to reintroduce democracy in Bangladesh. As a result, all political

activity was banned and the major cities placed under strict curfew.

Over the past year, not one but two former prime ministers, both of

them women, have been jailed.

Since the military-backed takeover in January, the government has

detained more than 250,000 Bangladeshis, with reports of torture and

killing rife. Apart from the political upheaval that's gripped the

place for a year now, Bangladesh is one of the poorest nations on the

planet. Half its population lives on less than a dollar a day.

To say the least, economically, geographically and now politically it's

a tricky place to carry on the normal stuff of life. But if there's

such a thing as a good-news story to be found here these days, you

might find it a short journey out of town in places like this, the tiny

semi-rural village of Dholla.

Dholla's a classic example of Mohammed Yunus's now world-renowned

poverty busting microcredit projects in local action.

We made it to Dholla, appropriately enough, by boat. We were, after

all, in Bangladesh's notorious flood-ridden Ganges Delta where most of

this densely populated country's people are crammed.

GEORGE NEGUS: Thank you.

The Grameen Bank was already open for business. The word 'grameen', by

the way, actually means 'village'. Our guide from the bank was the

general manager, Nurjahan Begum.

NURJAHAN BEGUM, GENERAL MANAGER, GRAMEEN BANK: So he'll put

down their

number and money, how much he's collecting.

They bring their cash each week and pay their loan money back.

NURJAHAN BEGUM: Yes. So he will write down in this passbook.

There's

the money.

Dholla's microbusiness women were gathered in this simple tin

shed to

pay the regular weekly instalments on their loans. They don't go to the

bank, the bank comes to them. They're all far too busy making money.

Hardly a fortune, it has to be said, but more than Bangladesh's dirt

poor villagers normally live on. The annual per capita income in the

country is just over A$500, with millions on much less.

WOMAN, (Translation): Yes, we had a very hard time. We had

just a small

meal every three of four days. Now we have no hardship at all.

You would have noticed the almost complete predominance of women here.

That's because something like 97% of the close enough to $3 billion

Grameen has loaned over the last 30 years has been to women.

GEORGE NEGUS: And no collateral? They don't have to bring

anything in?

NURJAHAN BEGUM: Did any of you need to offer collateral to get

a loan.

WOMEN, (Translation): No.

The reality is these modest village enterprises give a whole

new

definition to small business. In fact, they're the smallest of the

small, all of them built up over a few years starting with a

no-collateral microloan equivalent in takas, the Bangladeshi currency,

to a lousy couple of hundred Australian dollars. Grameen-inspired,

they're many and varied, be it sewing the country's traditionally

colourful saris, selling them locally at affordable prices, or handmade

mats from bamboo husks. No formal education or training, as such, is

required. Point being, these women and 6 million others just like them

throughout Bangladesh, have neither of these things. But, thanks to

their microbusinesses, they told us, now their kids will.

NURJAHAN BEGUM: So now she has a house.

What else have you achieved for your family?

WOMAN, (Translation): I have proper housing now. I have three

daughters, no son.

NURJAHAN BEGUM: She has three daughters.

WOMAN, (Translation): Two daughter already married, One

already goes to

the school.

NURJAHAN BEGUM: She's reading in class 7.

Precariously, if that's the word for being careful not to put

foot

wrong, we rounded off our visit Dholla with a quick visit to a business

the locals are especially proud of, a cow-fattening farm.

NURJAHAN BEGUM: He can earn per cow 10,000 to 15,000.

GEORGE NEGUS: So the men work on the farm with the cows, and

the women

still handle the loan money?

Were they very poor before?

NURJAHAN BEGUM: She doesn't have anything.

GEORGE NEGUS: Just a very, very basic life. Now they have a

business, a

thriving business.V\

Well, I guess you could say this has been a tantalising glimpse, a

crash course, if you like, into how this way of financing incredibly

modest small businesses, small village businesses like this one, and

how it least has some sort of impact on what the rest of us have always

felt as being a futile attempt to reduce the amount of poverty in the

world.